- Home

- Ginger Zee

Natural Disaster

Natural Disaster Read online

This book is dedicated to my late grandparents, Oma & Opa (Hilda & Adrian) Zuidgeest, George Hemleb, Paula Wesner, and John Craft—and to my beautiful grandma Clara Craft, who remains a wonderful part of my life. Without all of you there is no me—no mess—naturally.

Copyright © 2017 by Ginger Zee.

Cover images: ABC/Heidi Gutman

All rights reserved. Published by Kingswell, an imprint of Disney Book Group. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher.

For information address Kingswell, 1200 Grand Central Avenue, Glendale, California 91201

ISBN 978-1-368-01231-7

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

Chapter One: Runaway Bride

Chapter Two: A Weird Little Girl with Even Weirder Dreams

Chapter Three: The First Hint of Depression

Chapter Four: Otis/Flint

Chapter Five: WOOD TV

Chapter Six: Katrina

Chapter Seven: Brad

Chapter Eight: Interview in Chicago

Chapter Nine: Chicago

Chapter Ten: The Politician

Chapter Eleven: Trolls and TV

Chapter Twelve: Teaching and Science

Chapter Thirteen: ABC Interview

Chapter Fourteen: Fixing Myself

Chapter Fifteen: Cracking My Code

Chapter Sixteen: A New, Better Me

Chapter Seventeen: Transition to ABC

Chapter Eighteen: The ABCs of Travel

Chapter Nineteen: El Reno

Chapter Twenty: Ben

Chapter Twenty-One: Key West

Chapter Twenty-Two: Grateful

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Ten days before I started my job at ABC News, I checked myself into a mental health hospital. This is a compilation of stories leading up to and after that fateful decision that I hope will help demystify depression. This is the anti-Instagram, the raw, sometimes scary, and hopefully humorous life I have led so far.

This is me, a Natural Disaster.

I cover natural disasters, and I’ve struggled with being one in my personal life.

From Hurricane Katrina to California wildfires and blizzards in Boston, I’ve covered the nation’s largest natural disasters for more than a decade. I’m intimate with human reaction and interaction during Mother Nature’s greatest fury. Coincidentally, through that process, I have finally started to figure myself out and oddly found quite a few parallels.

Earth is just one big ball of energy that is constantly attempting to find balance. The poles are cold and the equator is hot. Earth wants so badly to equalize that difference. In doing so, it creates storms. Many of them are dangerous. But all storms are necessary.

This helped me realize that all I am is just one big ball of energy that will at no point be constant, even though that is what I constantly yearn for. We get average temperature or average precipitation only from having extremes. That’s what life is: a series of extremes. The sooner we can embrace that, the more peaceful I believe we can be.

Very few natural disasters catch us by surprise. We see them coming, whether it’s through technology or our own eyes. And with that time, we make choices that can determine our fate. Do we stay in our homes or decide to flee? Do we shelter in the basement or go outside to watch? And then there’s the aftermath. Do we let the natural disasters destroy us and consider ourselves victims of forces beyond our control, or do we find gratitude in being alive and being stronger for the experience? And most importantly, can we shift our focus off our own perceived tragedies and reach out a hand to somebody else going through the same type of storm? That’s why the title of my book is so meaningful for me. My job in some ways has helped me get through my own personal storms just by seeing the disasters as a metaphor for a universal human experience and has given me invaluable perspective along the way.

When I witness a natural disaster, I am particularly struck by the degree to which we are all the same. Natural disasters leave tremendous shock, destruction, and sadness in their wake. My biggest regret as a natural disaster is that I did, too. Most people walk around after the initial tragedy, bewildered. Then they often start acting irrational, looking for house keys to a home that is no longer standing, or standing in line at a drugstore that’s been knocked to the ground. Eventually, sadness and some level of acceptance sets in. Hopefully, in the final phases of grief, we realize we are grateful to be alive and that we need to shift our focus off ourselves and onto helping others. We’ve all seen the footage and pictures of the first responders and the ordinary people who put themselves at great risk to make a tourniquet out of a belt for a victim or swim into dangerous waters to bring a stranded boy and his dog onto a boat. It’s quite inspiring, and in a weird way it’s what convinced me to write this book.

Initially, I flinched at the idea of writing a “memoir,” because I don’t think anything I’ve done in my life makes me that important. But then I thought of all the natural disasters in my own personal life that I have survived, how I’ve grown stronger from them, and how I’d like to share those if there’s any possibility it will bring hope to somebody in the eye wall of their personal hurricane or comfort to other survivors to know they are not alone. No matter your storm, it never rains forever. It can’t and it won’t.

That’s where I am now. By no means do I think that I’ve figured life out or that I’m some model of perfection—but it’s not raining. In fact, it’s pretty sunny on my side of the street. I’m happily married and the mother of a beautiful baby boy, and I have my dream job. And while I still have a lot of road left ahead of me, I’m at the point where I can look back at all the so-called disasters of my life—the sometimes chaotic childhood, the failed engagement, the insecurities and people pleasing, and the abusive relationships, and just like when I’ve been lucky enough to watch a tornado approach, I can find the beauty and strength that was born from each of my “storms.”

I can now accept the here and now. I understand that life isn’t always full of sunshine. There are many rainy days. Clouds that persist for years at times. And even at this point in my life, where everything is quite bright, I know it won’t be like this forever.

I also know that because of the chaos I created, the natural disaster I used to be, I was forced to do the kind of deep, soul-searching growth that means there will never be a next time when I find myself crying and drunk under a bridge in Chicago. There will never be another time when I’m hiding under a hotel table calling the police because my boyfriend emotionally abused me.

I hope you get a good laugh—even at the sad parts, I do. Finally telling these stories feels good. I think even some of the people closest to me may not know all these details. But this is me. A natural disaster. And this is me finally being okay with admitting that.

I canceled my first wedding…twice. Which is why I will always watch Runaway Bride when it comes on cable. I’m not ashamed to admit that it makes me feel good about myself. Julia Roberts ran away four times from four different men, one of them being Richard Gere. My runaway technically makes me at least 50 percent more efficient and way less erratic than the goddess of romantic comedies. Unfortunately, at the time, I did not possess the kind of clearheaded confidence that would have allowed me to listen to my instincts and save everybody a whole lot of drama, pain, and security deposits by canceling my wedding just once. The fact that my fiancé, Joe, was a great guy, the kind of guy who fixes things and plays catch with the neighborhood k

ids—plus lets you watch Sex and the City reruns even during March Madness—made me think I was nuts.

On the other hand I wanted to be a meteorologist since I was a nine-year-old staring at the storms rolling in off Lake Michigan. I knew that the life I had seen for myself for close to twenty years—chasing tornadoes, jumping out of planes, swimming with sharks—probably wasn’t going to make me your typical mom, which is what I thought Joe wanted and needed. He was a solid guy, simple and sweet. He deserved the same. But that isn’t me, and it took a lot of time before I could be honest enough with myself to realize it. I also never gave him a chance to express whether that would or would not work for him or for us; instead I avoided confrontation and just let the engagement go on.

Joe and I were engaged for eighteen months—a long time by most standards—and that’s on me. We got engaged after only six months of dating, and we knew we needed some time before the wedding. I feel it’s important to mention this because there’s an idea in our culture that it’s the guy who drags out the engagement because he’s not dying to say, “I do.” But this was a joint decision, probably driven more by me. I’m not saying this is cool or that women should aspire to an inability to commit; I’m just saying women should be allowed to be as messed up and complicated as men. In fact, I don’t have one female friend who hasn’t had a time in her life when the last thing she wanted was to settle down. That’s why it’s a lot easier for a lot of us to date jerks. Somehow the problem resolves itself, and you (and by you, I mean me) don’t have to look in the mirror too long.

It’s just so much harder to break it off with a nice guy. It’s not just that you feel like a horrible person for hurting somebody so kind; you spend a lot of nights staring at the ceiling convinced you must be losing your mind, there’s something wrong with you, and you will definitely regret this one day. And this sucks. At least it did for me.

In my opinion, too often women are told that our ambivalence toward marriage is something we must work through, in therapy if necessary, so we don’t get left behind and spend the rest of our lives with a bunch of cats and a freezer full of Lean Cuisine. The truth is, we’re complicated, and learning to trust ourselves is so much more important than the pursuit of marriage. It took a while to learn to trust that Oprah voice that always told me to live my best life and embrace my “aha” moment. And that meant breaking up with Joe. Twice. Even after the invitations were mailed and the cake was ordered and—for the second cancellation—the guests were on their way.

As my wedding to Joe drew near, I was working as a reporter and meteorologist at WOOD TV in my hometown of Grand Rapids, Michigan. Even though I was on television, being a reporter was not fun for me, because all I’d ever wanted was to be a meteorologist. Besides, that’s what my contract said I was hired to do—report on the weather. Unfortunately, when I started at WOOD TV, all five of the meteorologists already on staff suddenly decided they had no intention of retiring or moving on as the news director who had hired me had anticipated. And since the station needed a reporter, and I was under contract, that’s what I was told to do. And I did it to the best of my ability. I wasn’t exactly miserable, but I wasn’t exactly happy, either. This is important as context for “the wedding that wasn’t,” because my restlessness at my job was feeding the flames of the restlessness in my relationship.

Now, please don’t misunderstand all this grown-up self-awareness to be anything but hindsight. Which is just to say, I am, as always, aware that I am a natural disaster, softened these days by my deep regret that I ever caused anybody in my path any grief or pain. Especially Joe.

Joe and I were in love, and in Grand Rapids, there’s a clear path: go to college; find a decent man; marry and have kids with him. And besides, he asked, and I have a hard time saying no. In fact, my friends and family say I can’t spell no, which is ridiculous. Of course I can.

Even today, as a big-ass grown-up mom/wife/career person, I’m still working on saying no when it’s appropriate. I feel like I just came into this world ready to say yes. People like to talk about being an old soul; well, I’ve always felt like a really new soul, like maybe it’s my first time here, so I want to try everything. That’s the kind of fearlessness that has unconsciously become my brand, and I love it. If a producer pitches me a story idea, I always say yes. The wilder the better. And while this is a great quality for my work life, it is maybe not so great for my personal life. The way I see it, if you jump out of a plane or paraglide through the Andes, the worst thing that happens is you die an instant death. But I’m a statistics gal, and statistically speaking, those adventures will not lead you to your death. But if you marry too young or marry the wrong guy, statistics are not kind. It can be the kind of slow death one might suffer if forced to ride a carousel endlessly. Pleasant and safe, but eventually a little dizzying and suffocating. This metaphor should give you a pretty good idea of where my head was at exactly six weeks and one day before my wedding to Joe.

There is standard etiquette in the wedding world that you have to send your invitations out at least six weeks before the big day, so of course I waited six weeks and one day before the wedding to send out mine. And less than twelve hours after they were dropped into the mailbox at my neighborhood post office, I woke up in a cold sweat. Let me just say that I hope menopause never brings me the kind of sweat I had that night, because it was awful. Making the night even more entertaining was an adrenaline rush that fight-or-flighted me into action. Suddenly, no more fear. Poof! It was gone. I snuck out of bed like a cat burglar, even though Joe always slept like a bear in the middle of winter. I pulled on some running sneakers and ran out the door.

It was still dark outside, and the local post office was three miles away, but I had no trouble running there, crying with every step. I had no plan, just a vague conviction that those invitations could not under any circumstance depart from that mailbox. After about ten minutes of wiping the snot from crying on the sleeve of my pajama top, a postman tapped me on the shoulder.

“Let me guess,” he said. “Sender’s remorse?”

“Yes,” I said. More snot, more wiping.

He took out a ring of keys from his blue pants and began to unlock the box. I began to hear angels sing. He was going to help me!

“This happens all the time,” he said, with a light chuckle like I’d just done something cute like dropped my ice cream on the floor.

I didn’t care what his point of view was on this matter, just that he was going to help. It did occur to me that perhaps the US Postal Service needed to vet their postmen a little more carefully if it was this easy to get them to commit mail fraud. But obviously I kept my mouth shut. The last thing I needed was for my accessory to come to his senses.

It wasn’t hard to find the one hundred oversized silver envelopes in the midst of the utility bills and birthday cards. I grabbed the envelopes in snotty fistfuls, and my postman helped. Clearly, and for whatever reason, he was all in. And when we had them all and he’d locked up the mailbox, he put his hand on my shoulder.

“Now you get going, miss. I have a feeling there’s someone at home you need to have a talk with.”

He was right. And in that moment, I wanted to marry this man for being so kind and helpful. I went in for a hug to thank him. He pulled back. The crime was over and he was moving on. Understood. Respect. I nodded and turned to go. I took my time going home, exhausted less by what had just happened and more by what was going to happen.

A few hours later, I approached Joe with the box of invitations, organized as if they had magically never made it into the mailbox. But he knew they had—we had done it together less than twenty-four hours before. He was understandably confused. In a few garbled crying words, I simply told him the truth: that I couldn’t marry him.

I remember his reaction as if it was playing out in this moment. Joe somehow managed to move through all the Kübler-Ross stages of grief in less than thirty minutes. First he threw a laundry basket, which was so out of ch

aracter (anger). Then he started saying we could go to counseling together (bargaining). Then he began to weep (depression). Then he realized that if I wasn’t ready, then we weren’t ready, and the wedding just wasn’t going to happen (acceptance). And finally, we landed on the big one. Denial.

“It’s cold feet,” he said. “It happens to everybody! Maybe you should talk to somebody. A pastor, your mother, a therapist. I’ll talk to all of them if you want. Just trust me, this will pass.”

And then he began to cry again. And I began to weep. And then the wedding was back on. I didn’t want to hurt him, and my instinct is always to do whatever is necessary to stop anybody from crying. Staying the course and trusting my instincts by canceling the wedding was just too hard. Lots of people besides Joe would be mad at me. My beautiful vanilla buttercream cake would never be eaten, deposits would be lost, plane tickets canceled, dresses returned. Joe’s version, where my anxiety was typical and would eventually pass, was way more manageable. All I had to do was make it to my wedding day, and I already had a strategy that seemed pretty darned clever.

For three weeks I subsisted on a rabbit’s diet of no more than a fistful of carrots each day. When you are very, very hungry, your whole brain focuses on that and it’s impossible to have any other problems, because it’s all about the carrots. As someone with years of an eating disorder under her belt, I can tell you that hunger can be powerful. Hunger has to be a big reason why cavemen did not need psychologists.

And then, about three weeks before the wedding, I went cherry picking with my oma (Dutch for grandma). Oma’s name was Hilda. She had moved here from Rotterdam in the Netherlands with my Opa, Adrian, and their son—my dad—in the late 1950s. Oma was a tall, hilarious woman who was known for her bluntness. When her weathered hands had been picking cherries for more than an hour, she shot me a look and popped a cherry in her mouth. Through her thick accent she said, “Sit with me.”

We had a deadline for cherry picking, because we were going to use the cherries to make jam as wedding favors, and imagining Martha Stewart’s approval brought me comfort in the midst of all this chaos. Oma had grabbed my basket when she saw I was concerned about the time. With her beautiful piercing blue eyes, she then shot me a second very serious look.

Natural Disaster

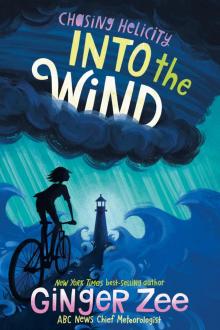

Natural Disaster Into the Wind

Into the Wind