- Home

- Ginger Zee

Natural Disaster Page 5

Natural Disaster Read online

Page 5

I imagine a thought bubble above Patti’s head when she saw me walk through the door in my Hillary Clinton bright-blue pantsuit with matching sensible heels that said, What was I thinking? Had I seen that thought bubble, mine would have read Game on. (My thought bubble also probably would have been a bright color and in all capital letters!)

As soon as I arrived, Patti welcomed me and brought me straight to the Weather Center, which is upstairs and separate from the studio and newsroom. It is its own little world where all the meteorologists at the station have their work spaces. A nondescript little cubby full of decades of experience and zest for meteorology. I immediately felt at home. The first person I shook hands with was my idol of all idols at WOOD TV, Terri DeBoer. Bright, blonde, and blue-eyed, Terri epitomizes Western Michigan (we are a very Dutch area). She can be polarizing on television, but the moment you meet this woman, you fall in love. As polished as she appears, her bright pink lipstick often gets on her teeth, and somehow it’s completely charming. She is the type of person who forgets her Velcro curler is still on top of her head until moments before she goes on television. Come to think of it, she may just be a bit of a natural disaster herself. That totally makes sense; meteorologists are way too quirky to be perfect.

Terri took me to lunch at the Bull’s Head Tavern. I had worked across the street in high school at a city country club called the University Club (think bankers and lawyers, with a place to work out and grab drinks), and certainly never would have guessed that one day I’d be having lunch with the famous Terri DeBoer, my coworker! We sat outside on a beautiful fall afternoon after her noon show. Terri is so recognizable, like a real-life cartoon character sitting on the sidewalk, that we hardly got through the meal. It felt like every other person that walked by stopped, recognized her, talked to her, and wanted a picture with her. And I was with her! I was going to be on TV with her. We laughed, and she was naughtier than I had imagined. She said all the things I wanted to say. She was who I wanted to be in the future. I still aspire to be more like Terri.

The next day I was assigned to my cubicle, and it wasn’t in the Weather Center, but rather in the newsroom with the main anchors, reporters, and producers. I was surprised to see I was sitting right next to the main evening anchor, Tom Van Howe. Tom was a Western Michigan staple, and to me he was a legend. I introduced myself to Tom, who I grew up watching and idolizing.

“Hi, I’m Ginger. I’m a meteorologist. I mean, I do weather.”

It reads better than it sounded. It sounded a lot like Baby in Dirty Dancing announcing that she “carried the watermelon.” His tan skin, handsome-older-man hair, and glasses made him irresistibly charming and delightful, and he graciously welcomed me.

“We needed a new meterologist,” Van Howe said. “That old Bill and Craig are starting to lose it.”

I knew he was joking, but appreciated the kindness.

And just like that, I was part of the team at Western Michigan’s number-one news leader: WOOD TV.

Every morning I put on one of my three primary-color pantsuits from Casual Corner and channeled all the drive and focus I imagined Diane Sawyer used to fuel herself in the early battles of her career. Every day I pitched story ideas at the nine A.M. staff meeting. My stomach did nervous flip-flops over and over as I stood before people who had been doing this for decades. I consistently got the looks from seasoned reporters and producers, or the finger tapping of Rick Albin. I hated that their annoyance got under my skin and made me question my confidence. I knew that, behind the eye rolling, there was a list of reasons why my ideas seemed ridiculous to these people.

However, I pushed forward. I still made my suggestions day after day, and when I got back to my desk after each meeting, I would make beat calls to local police and fire stations like a cub reporter from an old Cary Grant movie. Around eleven A.M., before the meteorologists and anchors were going on air, I left my cubicle and made the rounds of the newsroom, letting it be known that I was available for any and all assistance (not once had I even been asked to do a coffee run at that point). In the afternoons, I would order the same Jimmy John’s sandwich (the club with mustard instead of mayo) and go sit in the station’s library to watch old clips of the town where I grew up, the way a medical student might study a cadaver. I saw the evolution of storytelling from long, in-depth, frankly flat storytelling (as if you were reading a newspaper on TV) to what we then knew as the “MTV” brand of quick and flashy editing and graphics. I would furiously scribble notes just to look busy. I finished off the day in my cubicle writing a few imaginary e-mails, as if it had taken me all day to catch up on my correspondence. I was like the mom in the movie Room, who kept a very strict schedule to keep her sanity and never lose hope that one day the sun would shine and she would be free. I never imagined that sunshine would be a young, boisterous, six-foot-one-inch-tall reporter named Brad Edwards.

At random points throughout my life, Brad would be my lover, my father figure, my mentor, and my best friend. That’s a lot to handle, I know, especially since he is gay (see the lover part). So, let’s start with the friendship phase.

About four months after I started, Tom Van Howe suddenly decided to retire, which meant that there was an empty cubicle right next to WOOD TV’s newest and least-crucial on-air talent—me. It was a Monday morning. I was making my typical extraneous beat calls, and I felt a force move from behind me, slamming his messenger bag to the floor. I looked up. It was Brad.

“I’m having a cigarette in the parking lot. Let’s go,” he said.

That’s how Brad, my new cubicle mate, introduced himself to me. I wasn’t the least bit offended. I’d almost forgotten what a human voice sounded like. I had been a closet smoker in college to stay awake while driving (before I knew I was narcoleptic) and had a social cigarette here and there. So one cigarette with the potential of interacting with a real human within the confines of that WOOD TV edifice on College Avenue was heaven.

Brad is an acquired taste for most—he is blatantly honest with a sense of humor drier than Death Valley. I acquired that taste within the first drag of that cigarette.

Years later, I would ask Brad why it took him so long to talk to me.

“I couldn’t decide if your fashion sense was an indicator of your insanity, or sense of humor,” he said.

“Bold colors send a message of power and confidence,” I replied.

“Oh. So the answer to my question is both.”

I wouldn’t say Brad took me under his wing, but he did use to say things like “When we get out of here…” and “Don’t worry, you can trash him in your memoir someday,” that buoyed my confidence and made it fun to come to work.

Brad had worked in Lansing, Michigan, before coming home to WOOD TV, too. I say home because he grew up around Grand Rapids. He studied journalism and writing at Michigan State University and had already won Emmys and who knows what else as a twenty-five-year-old reporter. Don’t ever ask him to list his awards. Or do. He’s won so many Emmys he’s started giving them away to his story subjects. Without prejudice, I believe that Brad is the best writer in television news. He has a style and a voice that are unmatched and not seen by nearly enough people. What makes him special, in my opinion, is that his work has changed and touched the lives of so many people. His mission is simple but so hard to pull off: impact. It was inspiring to have a friend who was so respected at work, a friend who would always offer to help make my work better, and a friend who made me laugh until I nearly peed my pants.

Brad and I were like the bad kids in class. It seemed as if we were always getting in trouble for talking too much and for laughing too loud. Rick Albin actually sat in the cube across from us and devoted a lot of energy to throwing us dirty looks all day. To be fair, we were pretty obnoxious. Sorry Rick.

There was the time I walked in and had just had cut my hair short. Like, really short. It was an impulsive move based solely on seeing a network anchor with short hair and thinking that would help get me to

the top. It would not, by the way. It made me look round, dated, and just plain funny. But you couldn’t tell me that the night I got it cut. In my mind, I looked like a powerful woman ready to take on the world.

I got up that morning for work and styled it as closely as I could to the way the masters at Design 1 (the nicest salon we had in Western Michigan at the time) had done it. It looked a little off and nothing like the professional style, but again, I was perfectly pleased with my new Mariska Hargitay season-five-of-SVU do.

This was a life changer. Note: making large statements and basing them on absolutely nothing (like a new haircut) is a natural-disaster trait, because a haircut would never be able to live up to my expectations for it.

I marched into the building and flung open the door to the newsroom with confidence. Chin up, I set my purse on my cube and awaited Brad’s response. He was looking down, acting like he was actually busy.

I gave the “mhmm mhmm” cough that demands attention. And simultaneously, Brad and our friend Brett, who was the morning anchor, looked up at me and froze.

For that brief moment in time, I daydreamed of a world where they were high-fiving me for getting that grown-up do, in awe of my mature beauty. That daydream was suddenly demolished by the piercing sounds of roaring laughter. Brett and Brad were all but rolling on the ground laughing. Brett finally caught his breath and said, “You look just like the little Dutch boy. Why did you take your finger out of the dike? Now the town is going to flood.”

More laughter.

I plopped down in my desk and said, “Whatever, it’s powerful.”

Another shriek and giggle fit ensued. I looked up to see the only thing worse than Brett and Brad pointing and giggling: Rick Albin and the dirtiest look I think he had given me to date.

Brett sat right next to Rick, right across from Brad and me. It was a bad triangle, and I know Rick was over it. But we weren’t. We were just getting started.

That obnoxious friendship between Brad and me turned into regular cigarettes in the parking lot and after-hours script help where Brad would mockingly help me understand what a story actually needs, not what the typical reporter sees. Brad taught me to hear, smell, and touch a story, and make the viewer feel these senses as well. He was becoming my journalism mentor.

After a few weeks, Patti started sending me out to report on very small stories like a controlled burn (a wildfire set on purpose) or a rip-current drowning. I worked on the copy for those ninety-second pieces like I was Herman Melville polishing up Moby Dick. I still had my sights set on meteorology, but there were zero opportunities upstairs in the Weather Center. Thanks to Brad’s support and tutelage, I was okay with that for now. I’d watched enough sports with my dad and stepdad to know that a champion is defined by his challenges, not his victories.

I had no idea, but a defining moment would arrive soon enough with Hurricane Katrina. It was my first big storm to cover, my first gigantic challenge. And it changed everything for me.

On August 24, 2005, a tropical storm that had been upgraded to a hurricane just before colliding with Florida briefly weakened back to a tropical storm. Then it hit the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico, using that heat as fuel, rapidly strengthening. It was the eleventh hurricane of that season, and at the time, the forecasts were already looking grim for the Gulf Coast.

As a scientist, I found the storm exciting meteorologically, because we had no idea how tragic it was going to be. So I was elated when my boss, Patti, wanted to send me, along with Dan, one of the station’s longtime staff photographers, on a road trip to Gulfport, Mississippi, to cover the storm. This was the break I’d been waiting for. Finally, after six months of biding my time, weathering the low tolerance of my colleagues, trying to fill my days with beat calls and cigarette breaks with Brad, and being the under-the-radar team player, I was getting my chance. Patti was pretty excited about the assignment, too. In her own way.

“Show us what you’ve got,” she said.

Of course I went straight to Brad with this breaking news. He was underwhelmed. I pushed on.

“She has a lot at stake in my being successful. You have no idea the kind of pressure I’m under,” I told him.

Brad stood by me as I was packing the van with trail mix, water bottles, and a duffel bag of what I thought was an appropriate “on the scene” uniform—khaki shorts and fitted polo shirts with the station’s logo on them.

And then he laughed as I got in the van and started waving goodbye like he was my dad sending me on the bus to summer camp.

“I can’t wait to see you blowing down the street in your windbreaker. Watch out, Al Roker!” he cheered.

Dan and I made the drive in a little under seventeen hours. For an older guy who had every right to find me an annoying, overly excited little news puppy, and who definitely had no interest in covering any story outside about a two-mile radius of his house, Dan was pretty chatty. I knew that Dan was a Vietnam vet, but he never talked about those days. His mind had a way of jumping around, like a car with three wheels and no brakes, and I liked him. He accepted me—sort of the way you accept a flu shot every winter, but still.

As the storm made landfall, we were still a few hours from our target: Gulfport. We decided it was safer to wait and go in afterward, so we spent the first night in a motel in northern Mississippi.

As we arrived in Gulfport the next day, all my excitement about covering Katrina was washed away in an instant. It was way hotter and more humid than any place I’d ever been in my life. And it smelled. I still have PTSD about the way it smelled in Gulfport then. As soon as we got out of the van, every single one of my senses was immediately and viscerally assaulted.

The rotting bananas and chickens that had been dumped by the cargo boats emitted a scent beyond description. Because it was so hot and humid there, the body bags that were being collected were beginning to smell of rotting corpses. The refrigerated trucks had not yet arrived. The mold grew rapidly in whatever structures were still standing.

Then the sight—casino barges washed up onshore, as well as strewn-about mattresses, medication, keys, photo albums and books, and wandering dogs. The sounds of mourning and wailing and cries for help from the thousands of victims whose entire lives had been shattered overnight drowned any thoughts in our heads. We didn’t yet know that the taste of the precious, warm but clean water that we drank from the bottles we brought would soon be rationed. As the days passed, Dan and I began to limit our drinking to the van—we were self-conscious and wanted to be respectful and discreet, since we still had water to drink. We never took any from the church groups that arrived to help.

And finally, the sense of touch. Actually, this was the one sense that I avoided. There were nails and broken glass everywhere to step around, but the hardest thing for me to do was touch the people there. I saw a lot of journalists hugging the victims, but I couldn’t do it. At first I felt I was invading their space. In many cases we were the first people they talked to, the first human contact they had, and here we were, in their faces with a camera and a microphone. I had never done anything like this before, and it felt so foreign, so I was in a bit of a state of shock myself. I don’t think I had the wisdom and experience then to comprehend that there was a benefit to our interaction for the victims, too. These were just people, I am just a person, and often the outlet we were able to give them with the camera and microphone was the first bit of therapy available to all. Admitting what had happened. Making it real. And that hug, when genuine, can be incredibly powerful.

In those first two days, I avoided the uncomfortable interactions as often as I could. Instead, I stayed busy studying the science of the hurricane. I measured the waterlines and took notes on the storm’s depth, tracking the past, present, and future of Katrina. I tried to occupy myself by doing anything to avoid focusing on the human toll of this disaster, which was just so overwhelming I couldn’t begin to wrap my head around it. Dan, who had done this many times, and of course had been in a

n actual war, pushed me to start talking to people.

We started by knocking on doors, one after the other. Oftentimes, we got no response and moved on. People had either abandoned their homes, died, or maybe were just hiding because of the trauma they’d suffered. When somebody did come to the door, we asked them simply and as kindly as possible if they’d like to talk to us about what happened and how they had survived. I was consistently surprised by the number of people who wanted to talk to us. I particularly remember sitting with one family that had survived Hurricane Camille in 1969. It was unbelievable to me that they were going through this again.

One woman who lived in a house that was heavily damaged invited me to sit down and go through her photo album. It was hard to see the faces in the pictures, because the album was so waterlogged, but I knew they were family members. Her family had survived Katrina, but she brought me over to the shambles of a front porch. All we could see were slabs of concrete where houses once stood and where her neighbors had lived, and where, we would learn, many of them had died.

She carried her album outside with her and wouldn’t let go of it, hugging it like a child. Then she looked up from her album into my eyes and started to cry. And in that one moment, that one human exchange with this complete stranger, everything got real. For the first time in my life, I was face-to-face with the impact of a natural disaster. It wasn’t just a movie, or even something I was talking about from the safety of a studio. It was impossible in that moment with this woman to keep any kind of the journalistic neutrality I thought was required to be a professional. I simply had no idea what to do. In those very early days of my career, I had no real reporting skills and I knew it. All that brash overconfidence I’d felt back in Michigan, that surety that if I just got my shot, I’d knock it out of the park, suddenly seemed ridiculous. I had no understanding of the balance between listening and guiding people to tell their story. So I just sat with her while she cried. And maybe that was enough. To be a human in that moment, I had to learn to allow tragedy to wash over me, allow myself to feel her experiences and emotions. I was developing compassion and empathy.

Natural Disaster

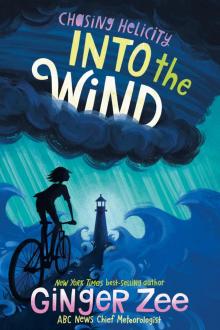

Natural Disaster Into the Wind

Into the Wind