- Home

- Ginger Zee

Natural Disaster Page 6

Natural Disaster Read online

Page 6

On our second day in Gulfport, we went out with the search and rescue team to look for dead bodies. We were using the satellite truck of our Indianapolis affiliate, and they had a hookup with the Indiana task force, a group that had come down with search dogs to look for bodies and make sure all the cars and homes were checked and cleared. Their job was also to go door-to-door and make sure no one still in their homes needed any help.

When you arrive at a pile of rubble that was once a home, the dog is instructed to go search for bodies or severed parts. When and if they return without finding anything, the task force spray paints a neon orange X on whatever is most visible (a front door, the hood of a car). On each side of the X is a code marking if there are any dangers inside (live wires, gas leaks, etc.).

We saw a lot of those codes being double-checked, which meant that the dead bodies inside had already been removed. The task force was very well organized and helped as much as they could.

After my first story aired that night on the eleven P.M. news back in Grand Rapids, I was criticized online for covering the storm. People had been writing to our station saying that I and the other reporters shouldn’t be down there, because we were taking away resources that the people of Mississippi and Louisiana needed. In my tag (the part after the scripted video that rolls), I assured our viewers that we hadn’t eaten, hadn’t showered, and would never take from those who had already lost so much. Every time I see myself at that moment (when I watch the tape back, even years later), I can tell I was changing. The story could have broken me, but I wouldn’t let it. I see such strength in that tag, and it makes me so proud that at that young age, with so little experience, I was not only telling those important stories but addressing the haters in the most mature way available. Since then I’ve experienced many similar online attacks (people thinking we should stay away from disaster areas), but what they don’t understand is that it helps the survivors to tell their stories, or it helps the city or state (when it’s a smaller-scale disaster) to make sure a state of emergency is declared so that federal funding becomes available for those who need it. In addition, I also believe it helps inspire people to donate to the victims of such disasters.

Over the next few days, Dan and I filed an average of six short (two minutes max) pieces a day. Katrina taught me how to tell a story. It was my boot camp. If you ask Brad, he’d probably nod and say that’s true, and then he’d tell you the story of one of my final Katrina pieces. In my defense, I was emotionally and physically exhausted when I filed the story on a flooded library with a voice-over on top of a book floating in a puddle. Not exactly a submission for the Edward R. Murrow Award, but it was all I had left.

It took too long for anybody to come and help the victims. Everybody knows that now. I saw firsthand that when FEMA finally arrived, they set themselves up under the cover of tents. But it was impossible to hide the helicopters that landed and delivered Outback Steakhouse meals to the agency’s personnel. It was horrifying and insulting. We were all starving. Granted, CNN was more prepared for a disaster than Dan and I with our grapes and trail mix, but I know that Anderson Cooper was not eating steaks and creamed spinach on assignment. In fact, he gave me a cup of soup on the fifth day of our coverage. Dan and I considered doing a piece on Outback Steak-gate, but there was no way we’d ever get FEMA to talk to us, and it was too crazy of a story to tell in an impartial manner.

I’d have to say that of everything I witnessed down there (and it was a lot), what broke my heart the most was watching crowds of people standing in line at a CVS that no longer existed. I’ve never seen people so abandoned, so desperate. For Dan and me, our situation might have been bleak, sleeping in a van and peeing in a corner behind a bank, but we knew we were going to leave.

What is it about humanity that makes people join a line for something that doesn’t exist? Is it the lemming phenomenon? Are we just pack animals who know our survival depends on being together? The look in the eyes of the survivors was so vacant—somewhere between a zombie and a character from the HBO show The Leftovers. Maybe the dead were luckier. Maybe they were standing in line because a line suggests hope; when you reach the front of the line, you get what you want. And these people had nothing.

Because of Katrina, when Hurricane Sandy hit seven years later, there were water trucks on every corner of Long Island, New York, in ten minutes. Because of Katrina, laws and regulations surrounding natural disasters changed so people wouldn’t have to make the choice between leaving their family pets behind and risking their lives to stay with them. Which doesn’t mean we handle natural disasters perfectly—we don’t. It’s just that Katrina was a watershed moment for natural disasters, and it changed me forever.

On our seventh day in Gulfport, a dog dropped dead at my feet. It was a little dachshund, and he was so dehydrated and sick; then suddenly he was just dead. And something inside of me broke. I had nothing left to give or offer as a reporter, and I called Patti and told her I had to come home. CNN gave us enough gas to get to Nashville. When we arrived, Dan and I debated checking in to our hotel for our first shower in over a week, or going out to eat. As soon as we saw the local Outback Steakhouse, we knew the answer.

We ate like starving animals. We drank like sailors on leave. We laughed and talked like old friends who had been through a war together and survived. It was a good, but strange, evening. I knew I’d earned my stripes, and although Dan didn’t put it into words, he didn’t seem quite as annoyed to be working with me as he had when this assignment began. I had taken the opportunity that was given me, I’d survived unheard-of conditions, and I had done my job to the best of my ability.

When I got back to the hotel room, I had a breakdown that took me by surprise. It was so much worse than the dog dropping dead that had made me come home. I realize now it was a form of survivor’s guilt. I got to go home. To a clean, safe place with food and water. Those people didn’t. And wouldn’t for days, weeks, and even years to come. I managed to get myself into the shower, where it’s always easier to cry because nobody can hear you and all the waterworks get washed away. You come out clean. I fell asleep, and we drove back to Michigan the next day.

I was surprised by my homecoming back at the station. Senior reporters I didn’t think even knew my name patted me on the back, complimented my work. A few of them even audibly said, “Good job.” Even Brad gave me the nod and offered me his own brand of “good job.”

“Boy, did you get lucky,” he said.

For the first time in my career, I was experiencing the respect of my colleagues. But I felt guilty about it, because it came at the immeasurable price of devastation. Still, as strange as it sounds, I’m grateful I got to witness and cover Hurricane Katrina. I’m grateful I got to meet the survivors and see firsthand the resilience of the human spirit at such a young age. I’m grateful that I got to learn that I am tough under pressure, that I can do any job when it’s put in front of me. I have covered many natural disasters since Katrina, and even though I’m a better reporter/journalist/meteorologist than I was back then, I know that Katrina was a baptism by fire, a coming-of-age, a loss of innocence that has made me who I am today.

Katrina also gave me perspective. It made me so grateful for every little thing I had. Everything, down to my shoelaces, meant more to me afterward. Life is so fragile. With that frailty, it’s an injustice not to feel happiness and live life to its fullest.

When I returned from Katrina, my wedding to Joe was less than a year away. But it was at the bottom of my priority list. Joe’s sisters and my best friends were constantly reminding me of dates and tasks that needed to be completed. But my mind was so far from the altar. I had seen how fragile life could be and how quickly a real natural disaster could end, or forever alter, our lives. I was inspired to celebrate life and never settle.

Simultaneously, my relationship with Brad was evolving from platonic gossipy colleagues to something more. But remember, Brad was gay. So that “something more” was super c

onfusing.

There were days where Brad would finish his work quickly, and I would have nothing to do. Our usual two smoke breaks became five, and we would play pranks and laugh so loudly in the newsroom that we actually got reprimanded by Patti. She took us into her office and told us that people were complaining and she needed us to settle down or she would have to separate us.

Nothing makes a grown woman feel more like a second grader than that discussion. So, Brad and I obliged, and took our communication to the Internet. We started Gchatting (using a new thing called Gmail) instead of actually chatting. And even though we were sitting right next to each other, something about text versus spoken word made the conversation mature into something more intimate. Our banal chats quickly unfolded into deep philosophical discussions about sexuality, religion, and love. I couldn’t wait to get to work every day to engage in our conversations. I would think about our discussions after I went home. I was so inspired by Brad and the dream world we were weaving that I often mentally left the life I was living. In what was essentially the basement of an asbestos-filled television station in Western Michigan, we allowed our imaginations to transport us to a world we created. It was almost as if we were writing our own screenplay and we were the stars. We started expressing our most far-fetched dreams. And then those dreams became hypothetical discussions of our dreams combined. We would banter about what our children would look like, what they would be named. We talked about fleeing the country, quitting our jobs, and moving to Europe. We named our make-believe château in Italy “La Rondinaia”; we even gave our fantasy nanny, Leonora, a soap-opera backstory. In this illusion, we had drivers, chefs, and private jets. This imaginary world was fun, yes, but now I know its main purpose was to fill a major void for us both.

Joe, as I’ve mentioned, was the absolute best man, sweet, simple, and full of love. Brad, my gay best friend whom I was strangely falling in love with at work, was the most complex, brilliant individual I had ever met. We were falling in love with the idea of being in love. With each other. Even though it made no sense in reality. Or did it? Could it?

Just before Brad moved into the cubicle next to mine, he had lost his father to esophageal cancer. He was a teacher, a sports official, his basketball number is retired and he is in the Grand Rapids Hall of Fame. More than once Brad read me the eulogy he wrote for his father’s funeral, and to this day, he speaks about him as the greatest human that ever walked this earth.

When Brad’s dad was taken, so was a part of Brad. All he wanted to do from that day forward was to live life like his father, Don “The Animal” Edwards. For Brad, as a gay man, being a husband and father seemed unachievable. But here was this mess of a young woman (me) who may just be interesting enough to marry, have children with, and even pretend to be straight for. Maybe?

I didn’t realize it then, but this was an emotional affair. Months passed where nothing physical happened between us. I honestly didn’t realize how much impact the emotional affair had on me, because I was never thinking of the life Brad and I had created as a reality. So I kept lying to myself and telling myself that I was making all my life decisions with Joe alone. But after the fateful night/morning when I ran to the post office to remove the invitations from the mail, the real crisis moment occurred.

I had anchored the weekend morning show and was meeting Joe at his parents’ house for Sunday dinner. This was the home that their four kids had grown up in, the home where they took Otis and me in as their own as soon as Joe put that ring on my finger. Their family always had Sunday dinner around one P.M. If it were an Instagram post, their Sunday dinner would have read “#FAMILYGOALS.”

On one particular Sunday, I came home from work before they returned from church and was up in the bathroom taking off my on-camera makeup when I heard them all come in. I don’t remember the exact quotes, but the conversation went something like this:

Joe’s oldest sister exclaimed, “Oh, Mom, do I smell glazed carrots? You know I love glazed carrots!”

The other sister: “Mom, you are the best. That turkey looks divine.”

And then his dad came in whistling “Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah,” and not ironically.

And then it struck me. They were too perfect. Not Stepford, freaky perfect, but just perfect saccharine sweet, honey wrapped in stevia wrapped in Sweet’N Low sweet. The problem was that I was not perfect. I was a closet smoking, big-city dreamin’, kinda messed up natural disaster, damn it! And there was no way I was ever going to be able to pull this off for a lifetime. I knew it. Now I know I didn’t love myself enough to even begin to think I could fit in with their family. Their consistency and joy did not fit the chaos I desired.

All I wanted to do was stand at the top of the stairs and scream, “You people can’t be real! BTW, I think I am in love with a gay man and I don’t want to marry your son.”

Instead, I sat down and ate those glazed carrots. They were really good.

Motivation can come from the strangest source. The next day I drove to work playing my Disney Princess best-of CD, as I typically did (this still happens, by the way, and it’s totally not weird). When the first song played, it hit me. I started sobbing and singing aloud to my favorite Pocahontas jam, “Just Around the Riverbend.”

I feel it there beyond those trees

Or right behind these waterfalls

Can I ignore that sound of distant drumming?

For a handsome, sturdy husband

Who builds handsome sturdy walls

And never dreams that something might be coming?

Just around the river bend…

Steady as the beating drum

Should I marry Kocoum?

Is all my dreaming at an end?

That’s the tone I walked into WOOD TV with that day. My dreaming was not at an end. I was going to take that chance and find out what was just around the river bend. I was not going to marry Joe.

I sat down and started expressing all of this to Brad online. After a few back and forths about how dull my life was going to be and how I was not Native American, I got up the courage to tell him how I was really feeling. I told him that our château, even if it was in Western Michigan, looked a lot more like the château I wanted to be in for the rest of my life. Instead of wanting to be with Joe, I found myself actually wanting to be with him. I felt comfortable enough to open up and ask him if what we were talking about could be a reality. He said yes. He was feeling it, too. I know now that this was also part of my natural-disaster trait of haphazardness and impulsiveness. I am an expert at jumping before thinking things through.

For a while, being engaged to Joe felt so safe in a “this is right and this will do” sort of way. But I was finally realizing I was not a “this will do” type of girl. The 2.3 kids with the minivan I saw Joe driving in my daydreams had been shattered by the reality that even my gay colleague could make me laugh harder and think more deeply than I ever knew possible. Brad opened a window into a world that I hadn’t even known was out there. He challenged me, and that is what I wanted. No matter what disaster I created along the way. This isn’t to say I don’t think Joe isn’t a great and inspiring partner. He just wasn’t the partner for me.

So, to tell the story of my calling off the wedding as I did at the beginning of this book without mentioning Brad was slightly unfair. But it would have been super weird to dive in without this background information. You might have put the book down right away. I may have, too. It’s a lot to take in. But I promise, as I mentioned, all this chaos of the natural disaster does end beautifully, eventually. So, there, now you know that not only was I finding myself and my inner voice when I called off my wedding, but I was also exploring the idea of a life with a gay man whom I was apparently attempting to date, marry, and buy a château with.

After the engagement was officially over, Brad and I did try to seriously date. Now, as best friends, we laugh about it. And we are both pretty grossed out by it, because he is gay. And he’s single, fellas.

/> My work on Hurricane Katrina definitely bolstered my confidence in reporting and gave me more opportunities to report for WOOD TV. By no means would it be fair to say that I was suddenly crowned Western Michigan’s “Queen of All Media”; I still had to fight hard for each piece, but I was grateful for the work.

I had what many would call a pretty enviable job, especially for my age. I would say that my overall state of being was that I was happy without intention, until I got the voice mail from Rick DiMaio.

Rick and I had met briefly at a conference in Madison, Wisconsin, about a year before the call. Because he was the chief meteorologist at the Fox station in Chicago and I was just at the birth of my career, our dynamic at that Madison conference was pretty much my being the fangirl to his Batman. I’m confident that our conversation that weekend didn’t go much beyond the merits of the crab cakes, but somehow his Rashomon take on that weekend was that I asked him a lot of pointed questions and he was impressed. But his message caught me by surprise. I asked Brad to listen to the message on my work phone so I could watch the look on his face just to make sure he wasn’t pranking me. Even then, I had to replay the message fifty times to process Rick’s invitation for me to come to Chicago, the third-largest market in the nation, and interview for a job opening as a meteorologist at the Fox station where he worked. My career so far had been PBS to radio to Flint to Grand Rapids. Chicago had been a ridiculous, out-of-reach dream. Until now.

Natural Disaster

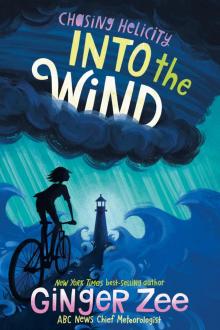

Natural Disaster Into the Wind

Into the Wind